Please check out my GameBoy emulator written in .NET Core; Retro.Net. Yes, a GameBoy emulator written in .NET Core. Why? Why not. I plan to do a few write-ups about my experience with this project. Firstly: why it was a bad idea.

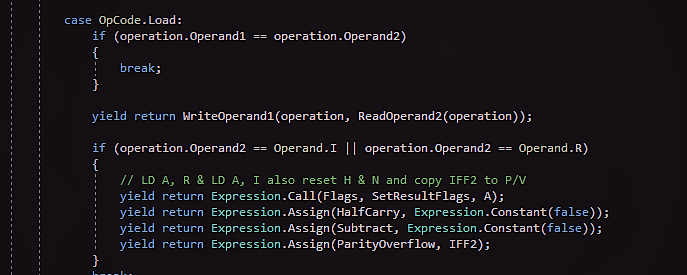

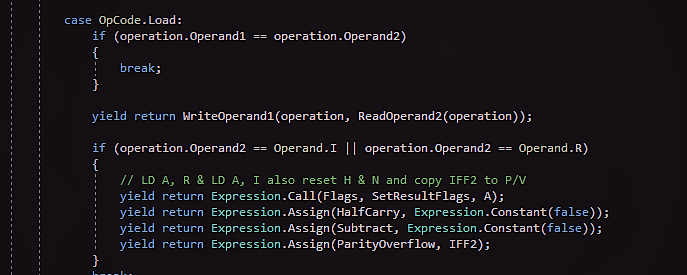

Retro.Net started as a programming exercise for me many years ago. I wanted a goal to work towards and wasn't happy with the boring examples that accompanied tutorials. Instead, I started a project that I knew would encourage me to continue writing code in my spare time whilst also including some electronics and retro gaming; a couple of personal interests. It has been re-written multiple times over the years and evolved into a successful product that actually plays Tetris at full speed. The CPU core is dynamically re-compiled into .NET with the help of the expression tree API and cached for speed. User interface is currently handled by ASP.NET Core, communicating over web sockets to a client written in Angular. The whole thing is geared towards a crowd gaming style of input.

Let's cut to it.

.NET is not an ideal platform for emulating legacy hardware.

C# does not (usually) compile directly to machine code, instead it is compiled into intermediate language (IL), which is a sort of machine code for the .NET runtime. The .NET runtime then uses just in time (JIT) compilation to run the IL on each target platform.

For server and enterprise software this has a load of advantages over compiling to native.

For all of these trade-offs, low level languages like C++ get some features that directly benefit emulation:

Timing is the number one issue then.

The GameBoy GPU drives the LCD at 60Hz whilst incrementing a register at 3 distinct phases of drawing each of it's 144 lines.

Some GameBoy software relies heavily on watching this register for timing.

So to achieve an accurate real-time simulation without graphical glitches or crashes, we must update it at the correct rate.

This requires a timer implementation having a resolution of at least 1/20th of a millisecond. Task.Delay is not suitable at this level of precision as it's maximum resolution is variable and can be in the order of 10's of milliseconds.

We must instead resort to inefficient thread blocking techniques such as spin waiting.

We can't even rely on the high resolution stopwatch for accurate blocking as some platforms don't provide an implementation.

Probably for these reasons, emulators have mostly been written in low level languages. This doesn't mean that it's impossible to run an emulator on .NET - just difficult to be accurate whilst also maintaining an acceptable level of efficiency.

However, there are use cases for emulators other than playing games where cycle accurate timing is not essential and in fact running the simulation as fast as possible would be beneficial. How about training a machine learning algorithm to play emulated games. For that we would probably want to run multiple instances, training multiple agents concurrently and each as fast as possible. Another example would be in the user interface of Retro.Net. This employs a crowd gaming concept, where all connected clients can vote on the next input. Cycle accurate timing is not essential as HTTP latency and the voting period length can be many orders of magnitude longer than the timing resolution required.

Next time I'll have a look at the core of the emulator behind Retro.Net, which uses a high level form of dynamic recompilation to emulate the Z80 derived GameBoy CPU.